How Understanding Proprioception Can Reduce Pain, Improve Performance, and Keep You Healthier Longer

Aristotle may have identified the five senses of sight, smell, taste, touch, and hearing in his treatise, On The Soul, in 350 BC, but science has come a long way since then. It’s not just the fab five anymore. Your body also has its own sensory Global Positioning System, something Nobel Prize-winning neurophysiologist Charles Scott Sherrington labeled proprioception in 1906. It’s derived from the Latin words proprius— “one’s own,” and percepio– “perception.” Put simply, it’s your ability to sense your body’s position in space.

Proprioception is dropping your feet on the floor when you get out of bed in the morning without having to look down; keeping your eyes on your laptop at work while you reach for your coffee without spilling it; switching your foot seamlessly from the gas pedal to the brake in the car without bending over to look at the floorboard. You don’t need to think about it, and you don’t need to see your arms, legs, or feet for any of it to occur without incident— it happens automatically, outside of your conscious thought. And though proprioception occurs on a subconscious level, there are things you can do consciously to assess your proprioceptive sense and identify ways to improve it.

Proprioception can be diminished for a number of different reasons, from aging to chronic pain to poor postural habits, leaving you at greater risk of falls or injury. The good news is that there are simple, practical things you can do to develop and strengthen it, enabling you to move and feel better in your own body. But first, what is proprioception?

What Is Proprioception?

Tune Up Fitness co-founder Jill Miller has been studying proprioception her entire career, but the easiest explanation for the concept came in an impromptu conversation with her daughter Lilah, who was four years old at the time. “We were in the car and I said ‘Lilah, isn’t it cool that you can just think about your knee, and you can feel it without even touching it?’ There was a pause for several seconds, and then she said, ‘Yes. Pretend your brain is a finger.’ It was incredible. I said, ‘You’re right. That’s proprioception.’”

Count on kids to find easier ways to talk about concepts neuroscientists have been grappling with for centuries.

Whether or not to categorize proprioception as an add-on to Aristotle’s five senses depends on who you’re talking to. Structural Integrator David Lesondak, author of Fascia: What It Is And Why It Matters and host of the podcast “BodyTalk with David Lesondak”, shares the view of many when he refers to it as a sixth sense. “Culturally and colloquially we’ve talked about ESP as the sixth sense forever, but proprioception is the legit sixth sense,” he says. “It’s related to touch, but it’s not the same thing. It underlies every movement and gesture.”

Physical therapist Adam Wolf, founder of The Movement Guild in Chicago and author of Foundations of Movement: A Brain-Based Musculoskeletal Approach, thinks of it a little differently. “I don’t think proprioception is the sixth sense,” says Wolf. “I think it’s one of three systems in the body, the other two being the visual (eyes) and vestibular (balance) systems. Those three sensory systems give the various parts of your brain information, and it interprets it so everything can work together. In that way your brain is like the ultimate virtual reality machine.”

When listening to different professional and scientific perspectives on the concept of proprioception, it can sound more confusing than it actually is, because it often comes down to semantics. Jennifer Milner, Pilates trainer and host of the Bendy Bodies podcast, puts it succinctly and humorously when she says “This is absolutely a conversation that can devolve into a fist fight if you’re having it in the right group of scientists. It’s a complicated conversation, but to me, it’s just your body’s awareness of where you are in space.” Even better, Millner comes through with a Star Wars metaphor everyone can understand; “In the original movie, Luke is training on the Millennium Falcon with the lightsaber. Obi-Wan puts the helmet over Luke’s head so he can’t see and says ‘Just sense it. Sense what’s going on around you.’ That’s Luke’s proprioception getting stronger.”

So why should you care about proprioception?

Whether it’s a sixth sense as David Lesondak believes, or one of the three sensory systems that drives brain-based movement as Adam Wolf describes, it’s foundational to how we understand and use our bodies. “Can you imagine living in a house and not knowing what the couch or dining room is for?” asks Lesondak. “That’s often how we approach our bodies. But the more we’re in touch with what we’re feeling, the more likely our body will become our friend instead of something we have to fight or struggle with to have it do the things we want. And to me, that’s the real benefit of understanding proprioception. It gives you confidence about how to improve it.”

Before we take a deep dive on all things proprioception, let’s take a quick look at how it compares to three other terms commonly used in the same conversation as proprioception. They are all different processes, but work together to try to achieve homeostasis in physiological function.

Jargon Alert

- Proprioception (one’s own): The body’s sense of its position in motion or stillness. Knowing where we are in space.

- Interoception (inside): Sensations that originate inside the body. Originally was narrowly defined as sensations from the viscera (the organs in the cavities of the body, primarily the abdominal and chest cavities), but has now become more inclusive of other sensations including heart rate, breath, and even the felt experience of emotions.

- Exteroception (outside): Sensory inputs that originate outside the body, including sight, smell, touch, hearing, and taste.

- Kinesthesia: A subtype of proprioception, but instead of position sense, it detects movement or acceleration in the body.

Source: Meredith Stephens, DPT, MS, PT, LMT, ATSI, BTSI

Proprioception and Daily Activities

Proprioception is part of every move we make, every minute of every day, and no anatomical part may be a better example of this than the ankle. The retinaculum of the ankle— or the fascial band around your ankle— has five times as many proprioceptive nerve endings as anywhere else in your body. Jennifer Milner describes how this plays out in something as simple as stepping off of a curb onto the street. “If you’re walking down the street at night and it’s late, maybe the curb is bigger or higher than you thought it was going to be, so you start to twist your ankle. If you have a lot of proprioceptors down there, then you have a lot of voices shouting back up at your brain, ‘Hey, you’re about to twist your ankle. Right yourself, and fix it before anything happens.’ Your brain thinks ‘Oh my gosh, I’m about to sprain my ankle,’ and fixes it. If you have poor proprioception, then you don’t have a lot of guys down there ready and willing to work, so the message gets to your brain too late and you twist your ankle. It’s the difference between having a 5G network and the Pony Express.”

Are you worried you might have the Pony Express in your ankle instead of a 5G network? Here are some easy things you can do at home to support proprioception in your foot:

For more tips and exercises on improving proprioception see below.

When Proprioception Goes Wrong

One of the easiest ways to understand proprioception is to hear the stories of those who’ve lost it, through injury or other causes. The most famous case is Ian Waterman, an Englishman who was the subject of the 1997 BBC documentary, “The Man Who Lost His Body.” Waterman was a 19-year-old employee at a butcher shop when a flu-like infection landed him in the hospital, and he woke up with a total loss of proprioceptive sense. The virus attacked his central nervous system and destroyed all proprioceptive sensory neurons, but left the motor neurons intact.

Neurons: Cells in the central nervous system that send and receive information to and from the brain.

The result was that Waterman’s muscles and limbs still worked, but he couldn’t feel where they were in space. “My limbs were dead to the touch,” he told the BBC documentary crew. Doctors told him he would likely never walk again, but he spent 17 months in a rehabilitation center, determined to avoid the wheelchair he was told he needed. Since Waterman couldn’t depend on proprioception to sense motion from his arms and legs, he had to figure out a workaround, and his eyes became his most valuable asset to regain the life he lived before the virus. In order to move any part of his body, he had to be able to see it while he moved it. “I had to look at everything to control it.” That meant looking at the floor and his feet every time he took a single step; it took him a full year to be able to stand safely. The damage to the nervous system was permanent, so to this day, Ian must focus intently on every move he makes with his body. Nothing happens automatically, the way it does for most people. The lights must be on at all times (if he can’t see what he’s doing, he may collapse), and his days are full of endless readjustments to his surroundings. Even something as simple as picking up an item at the grocery requires him to alter his stance for stability, otherwise a heavy piece of produce can throw off his physical orientation in space and lead to a fall. Despite all of this, Waterman has gone on to lead a full life, and has proven to be an inspiration to others who experienced sudden loss of proprioception.

Famed neurologist Oliver Sacks wrote about a similar experience he had with a patient in his 1986 bestselling book about neurological disorders, The Man Who Mistook His Wife For A Hat. Sacks treated a woman named Christina, who lost her sense of proprioception after a standard-protocol dose of antibiotics before gallbladder surgery caused acute inflammation, damaging some of her sensory nerves. While one hospital psychiatrist initially dismissed Christina’s condition as “anxiety hysteria,” Sacks and his team did a series of sensory tests that revealed a near-total proprioceptive deficit, similar to Ian Waterman’s experience. After Sacks explained to Christina the interdependence of the three systems of vision, vestibular (balance), and proprioception for body movement, the patient came to the same conclusion that Waterman did; her eyes must step in where her proprioception left her. She told Sacks, “This proprioception is like the eyes of the body, the way the body sees itself. And if it goes, as it’s gone with me, it’s like the body’s blind. My body can’t ‘see’ itself if it’s lost its eyes, right? So I have to watch it — be its eyes. Right?” As with Waterman, Christina’s damage was permanent, but as time went on, she was able to do many of the things she did before her hospitalization and injury, with accommodations.

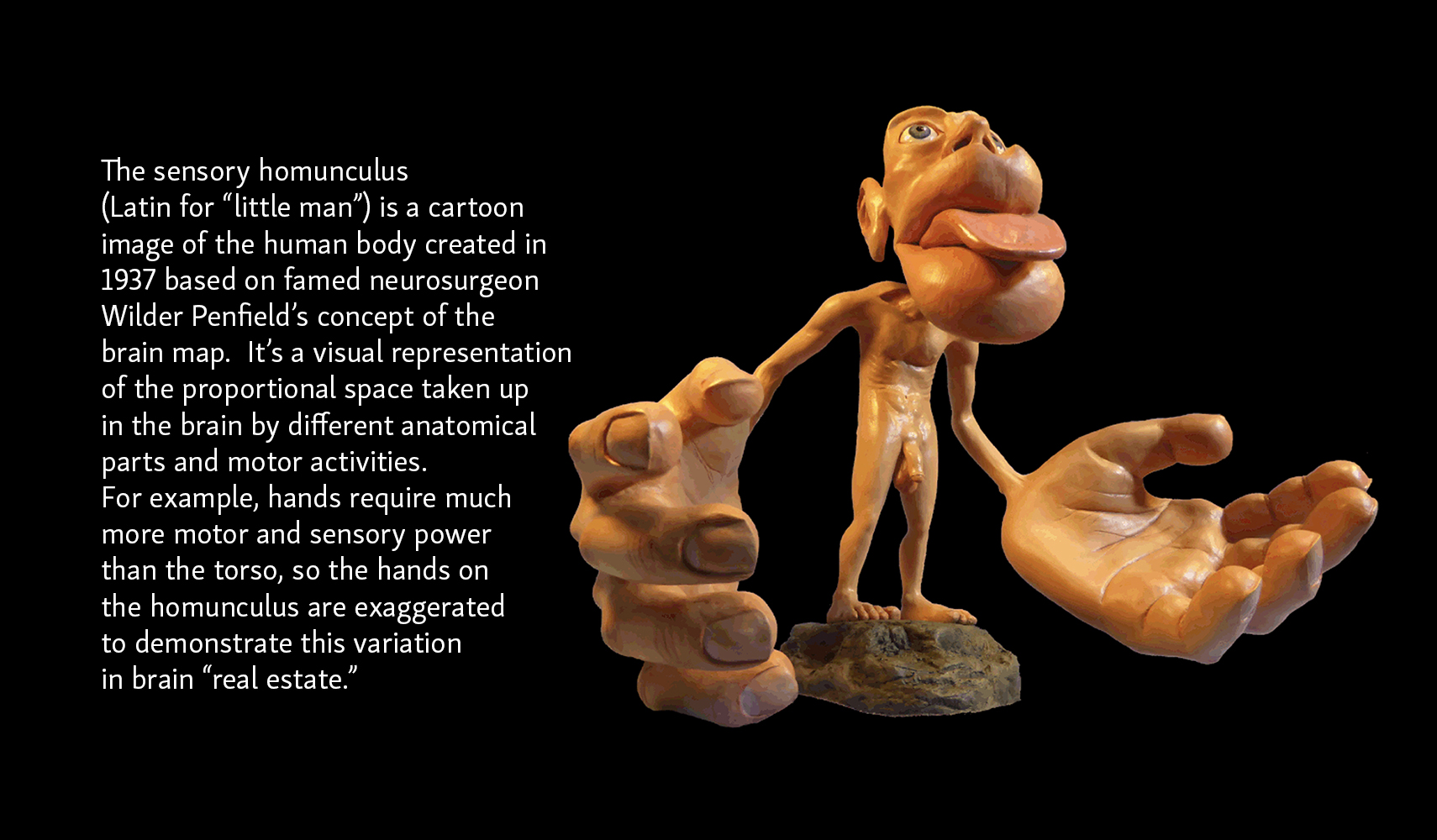

While Waterman and Christina are good examples of people who have healthy limbs but no proprioception, neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran has done groundbreaking work with patients who’ve lost a limb in an amputation or traumatic accident, but still maintain proprioceptive sense in that missing part of the body, a phenomenon known as phantom limb syndrome. Some of these patients experience the feeling of movement or pain in the spot where the limb was, and may complain that the missing limb feels locked in place, causing intense discomfort and cramping. In order to understand how this happens, we first need to understand that our brain has a sensory map that is spatially organized around the way we use our body. Certain parts of our body have more or less “space” in our brains, according to the level of activity. Dr. Meredith Stephens, a specialist in physical therapy, scoliosis rehabilitation, and healthy aging explains it this way: “If you’re a very good piano player, the representation of your hands in the brain map is going to be much bigger than it would be for me, because I don’t play a single instrument. If we think of it from a motor control perspective, when we stop moving things, we lose real estate in the brain. The map in our brain that helps us with the dexterity and movement of that part will shrink. Conversely, if we use something a lot, it gets more real estate in the brain.”

In his book The Tell-Tale Brain: A Neuroscientist’s Quest for What Makes Us Human, Dr. Ramachandran connects the phantom limb experience to the brain map. “Think of what happens when an arm is amputated. There is no longer an arm, but there is still a map of the arm in the brain. The job of the map, its raison d’être, is to represent its arm. The arm may be gone but the brain map, having nothing better to do, soldiers on. It keeps representing the arm, second by second, day after day. This map persistence explains the basic phantom limb phenomenon— why the felt presence of the limb persists long after the flesh-and-blood limb has been severed.”

Victoria C. Anderson-Barnes and her colleagues at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, DC hypothesize that this phantom experience is a result of something they call proprioceptive memory, suggesting that “the memories of the limb’s position prior to amputation remains embedded within an individual’s subconscious, and pain memories that may be associated with each limb position contribute not only to phantom limb pain, but to the experience of a fixed or frozen limb.” They propose that daily tasks and physical activity become part of a person’s proprioceptive memory bank, still embedded in the subconscious and easily accessible after amputation.

Dr. Ramachandran developed a technique to address the phantom limb experience called Mirror Visual Feedback (MRV), which he details in his book. “I placed an upright mirror in the center of a cardboard box whose top and front had been removed. If you stood in front of the mirror, held your hands on either side of the mirror and looked down at them from an angle, you could see the reflection of one hand precisely superimposed on the felt location of your other hand. In other words, you would get the vivid but false impression that you were looking at both of your hands; in fact, you would only be looking at one actual hand and one reflection of a hand.” Dr. Ramachandran instructed patients to move their hand, which “tricked” the brain into believing the phantom limb was moving as well, which often led to a reduction in phantom limb pain, or helped free the feeling of a frozen phantom limb. Though the exact mechanism for what produces the pain relief or unlocking of the phantom limb is unknown at this point, Ramachandran says in his book that he suspects the brain gets so many conflicting sensory inputs that it gives up and says “To hell with it; there is no arm.”

He discusses the mirror box experiment in more detail in his widely viewed 2007 TED Talk, 3 Clues to Understanding Your Brain.

How Does Proprioception Work?

So now we know what proprioception does, but how does it work? “You have these nerve endings called mechanoreceptors that are peppered throughout your fascial tissues at different depths,” says Jill Miller. “And they transmit information very quickly to your brain about where your parts are in relationship to each other.”

Mechanoreceptors: The nerve endings that relay specific touch and pressure-sensing information to the central nervous system.

“The mechanoreceptors are a system of five different sensory nerves, and they all have different functions,” says David Lesondak. “Some only engage when, let’s say you’re trying to lift a heavy object, and those mechanoreceptors that live near the joint spaces signal your brain about danger so you don’t overdo it. Some of the mechanoreceptors respond to fast, sudden movements and vibration, and some respond to long, slow traction or stretching. Others have a wide range of sensations from itching, to burning, to stinging, to the stroke of a paintbrush or feather, so they are sensations that are physical feelings. They’re not touch, per se, but they’re things we feel physically, and it’s all in the domain of the fascia and connective tissue. And what seems to happen is that when there is pressure or some kind of physical engagement of the mechanoreceptors, there is a very small piezo electric charge that causes the collagen fibers in the fascia to unwind in a particular way that transmits the signal to the brain. It’s a feedback loop that gives us a real-time assessment of how our limbs are working or not working.”

Piezoelectricity: the ability of certain organic materials to produce an electrical charge in response to mechanical stress. Piezo2 is one of the mechanoreceptors central to proprioception.

Scientists only recently discovered a very small number of people worldwide who are missing this piezo receptor— piezo2—which leaves them with very similar experiences to Ian Waterman and Oliver Sack’s patient, Christina, except the people without the piezo2 receptor are born with this genetic condition, instead of losing proprioception later in life due to an infection or other acute injury. According to an article published in Vox in 2019, a team of researchers at the National Institutes of Health and their colleagues around the world have only identified 18 cases, with the first two documented in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2016.

Dr. Wilbour Kelsick is a chiropractor and rehab specialist who works with private clients and athletes, and has been a member of the official staff of the Canadian National and Olympic teams for over 25 years. He says the key to optimizing proprioception is understanding it as something that doesn’t just live in the joints. “It’s a body-wide, integrated mechanosignaling system. That’s the most important thing to understand,” says Dr. Kelsick. “The way we’re taught anatomy and physiology is to look at the body in a very segmented way, but everything is connected. We move as a unit, and the gravitational field is acting on us as a unit. If a golfer is going to hit a ball, his vision is coordinating, but how much force is going to be in the feet? What is the arm going to be doing? The elbow has to talk to the knee, and the knee has to talk to the foot. The communication system has to work as a unit, and that’s what proprioception does.”

A key component of the “knowing where your body is in space” is adjusting to your environment. Jennifer Milner works with a lot of dancers, and noticed something about the way they move through rooms that broadened her understanding of how proprioception dictates how we interact with our surroundings. “I noticed when they’re not dancing, they’re hugging the furniture in the room; they’re walking close to a desk or chair,” says Milner. “I commented on that to a doctor friend of mine and he said, ‘Well, that’s proprioception. It’s just the body instinctively looking for something to tell them where they are. You put anybody into a room and they’re going to walk close to the table or close to the chair. Very few people are just going to wander through the open space.’ So it was fascinating to me to think of something bouncing off of myself, like sonar or radar.”

Take a minute and notice your own habits when you walk through a room. Even if the room is big, do you find yourself walking close to the wall, or near objects or furniture in the room? Do you bump your leg on the coffee table in the living room even if there’s plenty of space for you in all directions around it and you didn’t need to be so close to the table in the first place? That’s your body looking for something to tell it where it is.

Proprioception and Pain

Another practical reason to understand the concept of proprioception is its connection to pain. An increase in one inevitably leads to a decrease in the other. “Increase of pain is going to result in a loss of proprioception, period,” says Jill Miller. “Even if you don’t think you’re losing coordination, as your pain levels increase, your proprioception decreases. That’s just the way they work.”

Think of the brain map outlined earlier (the sensory homunculus), and the amount of space each part of your body takes up in that map. Pain has a direct impact on it. Adam Wolf summarizes it this way: “We know that immediately upon pain, the chemistry in your brain changes, and over time, that results in less representation of that body part in the brain. So that means if you have pain at a joint, either from a sprain or surgery, you’re going to have less proprioception at that body part.”

Part of the reason the brain chemistry changes is because pain changes the way we use our body, so the feedback loop between the mechanoreceptors and the brain is interrupted. “When we feel pain, we tend to not want to move the area because we don’t want to jar it and make it worse. It’s instinctive,” says David Lesondak. “And, unfortunately, if we do too much of that, it shuts down the proprioception. But if we can slowly induce more proprioception, the pain starts to recede and new opportunities for movement are created.”

A natural consequence of having a good proprioceptive sense is that you are better able to avoid situations that lead to pain or injury. “Proprioception is like a pain gate,” says Dr. Wilbour Kelsick. “If you think about proprioception in terms of maintaining kinesthetic sense, dynamic stability, and control, it prevents the body from getting to the extreme range. Because if the body has no sense of how far it’s going or how much things are being stretched, there is pain right away. Proprioception is like the guard that says ‘I’m here, because if I’m not working, things are going to go crazy and the body will send disinformation into the central nervous system.’”

Things That Can Negatively Impact Proprioception

- Poor postural habits

- Chronic pain

- Musculoskeletal injuries like sprains, broken bones, or torn ligaments

- Surgery

- Scoliosis

- Neurological or movement disorders like Parkinson’s Disease and Multiple Sclerosis

- Conditions that can result in neuropathy (nerve damage), like diabetes, infection, or vitamin deficiency

- Diseases of the fascia like Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome

- Aging

- Hypermobility

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome is an inherited disorder that causes hypermobility of the joints because of an abnormality related to collagen protein. Collagen is a key component of fascia, and if it’s not producing or processing normally, the mechanoreceptors can’t effectively participate in the feedback loop with the brain to support healthy proprioception. Not everyone who is hypermobile has EDS, but many still experience hypermobility in their joints and struggle with proprioception. “Some with hypermobility don’t always sense when enough is enough,” says David Lesondak. “They might go too far because they’re not getting enough feedback in the mechanoreceptors of the fascia.”

Jill Miller has been hypermobile her whole life, culminating in a total hip replacement at the age of 45 in 2017. The dramatic surgery upended everything she thought she understood about her own proprioception. It set her on a course that would bring her back to herself, and help others who have been in similar situations.

Desk Life and Proprioception

Even if you don’t have hypermobility or another underlying condition that negatively impacts proprioception, modern work life can have a dramatic impact on your proprioceptive sense. If you sit all day long at a desk, it’s important to be proactive about enhancing proprioception so you can reduce the risk of injury.

Dr. Aracelly Latino-Feliz is the founder of The Movement Therapy Institute in Florida and sees how this impacts her clients. “Even if you’re a healthy person, if you’re sitting in a chair for six or seven hours, your body is adapting to being in that position,” says Dr. Latino-Feliz. “Your proprioception will be altered after sitting that long. So you need to understand how it affects your performance so you don’t get injured when you go for a run after work.”

If you’re living the desk jockey life, there are some quick things you can do after work to bring your body back on board, and boost proprioception before you work out. First, show some love to the front of your hips and thighs, which have been curled up in a seated position all day.

Another important area to “wake up” is your glutes, which have borne the brunt of your long days in the same chair, participating in one zoom meeting after the other.

Test Your Proprioception At Home

Are you curious about your own proprioceptive abilities? There are some easy things you can do at home to gauge proprioception, and this allows you to discover parts of your body that need more attention. When you do a proprioception self-test at home, you may find that there are areas that don’t cooperate the way you expect them to. Jill Miller calls these body blind spots. “These blind spots are areas of overuse, underuse, misuse, or body confuse,” says Miller. “And it’s the confusion that I personally find the most intriguing, because it’s a failure of your body to give you feedback about where it is.”

Here’s a simple balance test you can take at home to gauge proprioception:

How To Improve Proprioception

The most exciting news about proprioception is that there are a lot of things you can do on your own to maintain or improve it. It will give you a better sense of how your body is moving, reduce pain, and reduce injuries. “When you think about it, we cultivate our senses, don’t we?” says David Lesondak. “People can cultivate a phenomenal palate for wine, or particular types of spices, or certain kinds of auditory or visual acuity. It’s the same thing with proprioception. It’s a sense you can cultivate, and the more you cultivate it, the more exquisite it can be.”

Tips To Improve Proprioception

-

- Move. Hike, walk, run, dance, do yoga, or any other physical activity that you enjoy.

- Slow down. If you are trying to correct a movement pattern that has been altered due to injury or surgery, slow it down and take time to really perceive the information coming into your central nervous system.

- Do movement work in front of a mirror. This will give you additional visual input to help with error correction. Seeing yourself out of balance helps you make the right positional change and strengthens the brain/body connection.

- Do weight bearing exercises.

- Try fascial bouncing. Jump up and down 50 times (or stomp your feet if you have arthritis or other pain) to wake up your entire connective tissue system.

- Walk barefoot on uneven surfaces. The beach, sand boxes, or outdoor areas with small pebbles give your feet opportunities to walk on something other than concrete in stiff shoes.

- Challenge your balance. Face the wall and stand on one leg. Hold a small ball or washcloth in your hand and write the letters of the alphabet on the wall with your eyes closed.

- Breathe. Use your breath to heighten awareness of your ribcage, noticing the expansion through your belly and the rest of your body.

- Touch. Bring awareness to any part of your body by touching it with your hands, therapy balls, soft foam rollers, or other props. Dry brushing your skin and tapping also heighten sensory inputs.

If you want to try a proprioceptive exercise that puts all of these concepts together, giving you a practical sense of how your tissues communicate with your brain to move your body, try one of Jill’s favorite moves, propellor arms:

Understanding proprioception and doing the small daily or weekly activities to support it can have a lasting impact on your health and mobility. Aging is unavoidable, but how we age is up to us in more ways than we often understand. You can be your own health care provider today, and reap the benefits for decades to come. “Prevention starts now,” says Jill Miller. “Slips and falls are the most deadly injuries to people over the age of 80. A fractured hip is the leading cause of death in the elderly, and those fractured hips come from slips and falls. And slips and falls happen because of a lack of proprioception and coordination. You can begin building your confidence and your body competence now.”

David Lesondak believes understanding proprioception allows your body to become your best friend. “When I work with my patients, I often hear the word want. ‘I want more confidence in my body to do X.’ And they get to the point where they feel like they have a new relationship with their body, and it’s their friend now. And to me, that’s the secret sauce. That’s the real gift you get from proprioception.” For even more on building proprioception, see Jill Miller’s new book Body by Breath.

Ready for more?

Now that you have a better understanding of what proprioception is, here’s a quick introduction to its sister sense, interoception. If proprioception is understanding what’s happening to your body in space outside, interoception is what’s happening inside. And just as you can take matters into your own hands to improve proprioception, there are things you can do to support interoception. Here’s a look at what it is, and how you can enhance it.

Read More on Tune Up Fitness

Thank you for this extensive, in-depth and fascinating article! I have learned quite a bit about proprioception in the last decade but this article summed up the subject eloquently and clearly for me, at a level that I can make it accessible to my trainees.

The fact that the retinaculum of the ankle has five times as many proprioceptive nerve endings as anywhere else in our body was new to me.

I was an active girl in the 70s and 80s – I played basketball on a team, soccer for fun and trained in karate for many years. I sprained my ankle repeatedly during those years and during that time all we did was wait for it to pass and get back to sports. We had no rehab, nor strength or conscious movement classes.

Back to the article – I learned about the interconnection between pain and proprioception and about Proprioceptive lag – so interesting.

Thank you also for the simple tools. I’ve come to appreciate them more and more since I took my first online course with you in the end of 2020…

I appreciated how PT Adam Wolf described the way that sight and the vestibular system work in concert with proprioception to allow the brain to “map” our position. I think of Simone Biles twisting and rolling in the air, what an amazing system this is! It is interesting to learn that the ankle retinaculum has the most proprioceptive nerve ending of any place in the body, and that “waking up” these proprioceptors can help prevent ankle sprains. I am inspired to work more on ankle proprioception for myself and with my students.

I have only done the roll out on the quads without the block and that usually is uncomfortable with the compression in my back. Trying this with the block and the coregeous ball made a HUGE difference.

I also have never heard Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. I wonder if I have it! I have 1 hip that is worse but than the other and it pops out of the socket regularly. Reading about the stories about tit hose who lost their proprioception is incredible and i am amazed at the ability of the body and mind to push through and find solutions that work. Gives me hope and faith!

The points about how habits like sitting too long can weaken body awareness really resonated. I appreciated the straightforward tips, like barefoot walking and balance exercises, for reconnecting with our bodies in a practical way. Such an insightful read!

Children should define everything in the world! I love the Lilah in the car anecdote in this article. I also appreciate that I now have another podcast I’ve subscribed to because of this blog – BodyTalk. I am fascinated by the factoid that the proprioceptive nerve endings in the ankle are 5 times that of other areas of the body – it makes so much sense!

It took me many years of practice to learn the hard way that the experience of “tight hips” can actually be from protective neural tension. I could easily contort myself into all of the “advanced” shapes and yet still felt exceptionally tight. My body was signaling the need for additional stability & strengthening rather than more flexibility & opening long before I learned to listen accurately!

My understanding of proprioception is widened by the observation of dancers moving through a space and instinctively “hugging the furniture”, and the idea that we are naturally magnetized to the physical parameters around us for positioning reference. New awareness to play with! And I love that we are able to map and grow our proprioceptive capacities.

Great article. I appreciate the many resources provided in this article and look forward to exploring this topic more thoroughly.

This is a great primer on proprioception! I will definitely be sharing it with clients 🙂

I especially appreciate the sensory homunculus and the idea of a body-map that lives in the brain. Really interesting to explore all the ways we can create a more detailed/accurate map using the other senses (i.e. touch, vision).

This article does an incredible job of shedding light on proprioception, a sense that often goes unnoticed but is so vital to our daily lives and overall well-being.

It’s fascinating to realize that our body has this built-in GPS system that helps us navigate the world without even thinking about it. But what struck me most is how easily this sense can be compromised by factors like poor posture, chronic pain, or simply aging. The idea that we can actively work to improve proprioception through simple practices like barefoot walking, balance exercises, and mindful movement is empowering.

The stories of individuals like Ian Waterman, who lost their proprioceptive sense, highlight just how crucial this sense is—and how much we take it for granted. It’s a reminder to cultivate a deeper connection with our bodies, not just through movement but by paying attention to how we move.

I also loved the practical tips provided for enhancing proprioception. Incorporating these small, mindful practices into our routine can have a huge impact on our physical health, especially as we age. The connection between proprioception and preventing falls in older adults is particularly eye-opening, reinforcing the importance of maintaining this sense throughout life.

Thank you for such a comprehensive and engaging article. It’s given me a whole new appreciation for the subtle but powerful ways our bodies keep us moving safely and efficiently every day.

I talk about proprioception all the time. I love the fact that it’s felt like years since the last time I stumped my toes on a coffee table (knock on wood) also the depiction of the homunculus is on of my favorite so profound and as a visual learner having that really helps to understand where the brain dominates its direction of neural focus. It’s on of the reason Ranunculus is my favorite flower. But this dive into interception at the end is where I would really like to expand. It really makes me think of John F. Barnes facial work. When I started to deeply feel this unwinding in my muscles and organs it was like a light bulb turning on and was the most profound experience I’ve ever had literally feeling my diagram contract and relax. Feeling that there is a natural way my muscles want to move I just have to listen to them and follow.

Wow this is a great, comprehensive article to help me think more deeply about proprioception. Thanks for the little tests – a bit humbling. As someone who moves a lot, but also sits a lot at a sedentary job, I didn’t realize that sitting for extended periods has a negative effect on proprioception. I am planning to talk the importance of proprioception to my pilates class with older women, and introduce exercises like propeller arms, to help improve proprioception.

This was a great beginners guide to proprioception. Throughout my growing up, I saw myself as clumsy, something of a family trait. Though I was introduced to yoga early in college, it wasn’t until my late 20’s, and especially my first pregnancy, that yoga became an anchor into my body and my physical awareness. I have always been hypermobile but it wasn’t until I was challenged with “holding my body in space” that I understood my real lack of proprioception. Reading this article as lit up so many sparks for me and I can’t wait to delve further into the subject!

Thank you for the in-depth article about proprioception. I’ve been interested in the idea of being aware of where and how your body is in space for a while now. I’ve observed that proprioception worsens dramatically when we are under emotional stress. On the other hand, physical stress such as exercise improves our proprioception. I can’t help but think about people with certain conditions such as Multiple sclerosis…There is so much to be explored and I hope that one day soon there won’t be such a thing as permanent damage to the nervous system.

I’m watching the slow process of learning guitar get a bit easier week by week, and I realize now it’s not just in remembering where to put my fingers, but also the proprioception of placing the fingers and how much pressure is needed. You always hear ‘practice makes perfect’ but the concept of gaining real estate in the brain described in this article is really interesting and a different way for me to think about learning.

As a desk jockey, I will definitely be revisiting this page after work.

Proprioception has fascinated me for quite some time. It’s very exciting to be able to see the benefits of specifically training it, because neurological changes can be so dramatic and be realized relatively quickly. Several things brought up in the article especially interested me – one of them being how it’s a guarantee that proprioception will decrease because of an injury. I’ve experienced that myself, and it reinforces how part of rehabbing an injury MUST include proprioceptive training. Also, Dr. Ramachandran’s Mirror Visual Feedback with the people with phantom limb pain is incredible. His TED talk is absolutely on my must watch list.

It’s so important to stay active as we get older, in both brain and body. And the brain and body are absolutely connected – in more ways than we can know.

Wow! I had such a lightbulb moment with the mechanoreceptors and brain map. I work with aging adults and knew that lack of muscular and joint movement created rigidness, but had no idea that lack of moving a part actually causes the brain map of that region to shrink lessening our control and activation.

I appreciated the depth this article went into when describing proprioception. Even though most individuals understand what proprioception means, many are challenged to really understand where their body is in space. Having worked with individuals as a Clinical Exercise Physiologist for many years I have worked with numerous individuals who really struggled with this concept. Looking back in hindsight, I can see now that this may have a neurological component for some, and I wonder what role trauma could possibly play in this? I have worked with those who experienced trauma and proprioception was the most difficult thing for them to grasp and relate to their own body.

My lack of proprioception led me to knee surgery, which ultimately let me to yoga and finally to Jill Miller! Throughout elementary, middle and high school, I considered myself to be unathletic and uncoordinated. In college I started running, and for the next few decades become a cardio junkie. I did cardio irresponsibly, never thinking about crosstraining, stretching, or being aware of my alignment. When I was 40, I had arthroscopic surgery on both of my knees. I was freaking out because the doctor told me that if I continued to do what I was doing, I would be headed for knee replacements in the next 10 years. Budgrudgingly, I went to a yoga class and started swim lessons. I shocked myself by getting into both! Through yoga, my awareness of my body increased, and I started to freak out less anytime I felt a little ache or pain. I found that the body awareness I gained from practicing yoga helped so much with swimming and functioning in my daily life. Completing the Body by Breath (r) and Roll Model (R) Method Trainings with Jill Miller and now doing the Tune up Yoga training is kicking up my understanding of the body and my own proprioception to a new level. As it says in the article, proprioception is so important for healthly aging. Now that I am 53…healthy aging is is on my mind (constantly, lol). I have also been learning a lot about hypermobility and hypermobility syndromes (highly recommend Libby Hinsley’s Yoga for Bendy Bodies with a forward by Jill!). I teach a class in a very hot studio which attracts many bendy people. I used to feel like clients were ignoring me when I suggested that they bend their knee if it was hyperextended. While it is true that they still could be ignoring me, I now understand that when you have hypermobile joints, it is difficult to sense an end range of a pose (like a hamstring stretch). Therefore, it may not be possible to sense when a join is hyperextended. This has been extremely helpful when I work my clients.

I use the Roll Model method in my Personal Trainings. One of my clients had a long-term inflammation in her elbow joint due to overexertion of her hands and forearms by excessive handicrafts such as sewing, knitting, gardening.

She was initially treated with all conventional methods: shock wave therapy, ibuprofen, homeopathy, osteopathy up to total immobilization… Unfortunately, the inflammation remain subliminally maintained. At this time we started with the rolling methods on her hands and very, very soft and slightly shearing of her forearms. It was the first time she noticed the extreme tension in her hands… Since then she has a much better awareness (proprioception) of when she is overusing it. With the roll outs the inflammation went down and so did the pain, the shoulder area relaxed. The new proprioception helps her to use her hands appropriately.

It was really interesting to read about proprioception and develop an appreciation for it that is much deeper than I originally thought. I knew it was important, but reading about the 2 people that lost it and how they needed to compensate was eye opening. I also was unaware that you could “train” to improve proprioception or that it was related to interoception. I developed a new appreciation for this sense and its importance from this article!

I really enjoyed practicing the balance propriocetion ! It was challenging. Like all the other suggestions this will be a great tool to help others to get some understanding of proprioception. Ty

It’s an interesting relationship between pain/immobility and decreased proprioception. I think YTU ball therapy is a great tool to bring awareness back into relatively immobile tissues – a perfect example that I see repeatedly is in the feet. Almost all clients that wear traditional “regular” toe box shoes have initial difficulty in separating movement of the toes, and also in isolating movements of the big toe of one foot, without clenching or moving their fingers or other feet. The foot rollout is one of my favorites, its immediate gratification in practicing foot proprioception, something that is greatly diminished in most people wearing conventional footwear.

Thank you for highlighting that proprioception is both body-wide and integrated. It is true that the body moves as a unit, though often we view its parts as separate – even when thinking about the proprioceptive sense.

Great article on what proprioception is, and how having keen proprioception factors in to balance and stability. I also appreciate that this article lays. out the inverse relationship between chronic pain and proprioceptive ability. The longer one experiences pain, the greater the loss of our ability to know where are limbs are in space. I also found the stories of people who lose proprioception fascinating, and that they can overcome the limitation by using eyesight and seeing where limbs are placed.

Excellent explanation of proprioception. I appreciated the references as they make it easier to explain to students

Interesting note about injury decreasing proprioception…although it makes sense because it is an injury, I would also think that it might increase proprioception because people become hyperaware of that body part. Similar to how it said that when we walk into an empty room, we are tempted to go near objects so we feel “safer”, people with injuries will often stay away from things that might bump/fall on their injured part. But maybe there will be parts in the injured area that will lose proprioception while not being used.

I’m fascinated by the relationship with the piezoelectric signals in he fascia and proprioception. I picture little electrical impulses mapping out the spider web network of tissue in the dark for our brain to be able to ‘see’ our body. It’s like a scratch-to-reveal game that’s always morphing and changing as we use our bodies differently day by day. The part about injury and other issues changing our maps makes sense too, that the file is always updating in real time.

Great article, thanks.

I really enjoyed this article and all the detailed scientific/medical references interspersed with Jill’s videos for building proprioceptive awareness. The Ian Water BBC video is a dramatic example of the role of proprioceptors in control of movement (muscle length, muscle tension, joint position). I was curious about Jill’s comment that pain impacts proprioception. What is the evidence. There are a small number of people that have a genetic mutation (congenital insensitivity to pain) that leaves them unable to sense pain. Are they better at proprioception? Here is a link: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK481553/

The body’s internal mapping system is truly fascinating and almost mystical. Knowing where we are in the world and being able to orient ourselves/our body in time space keeps us grounded secure and safe. And like most systems we can tend to it well so as to grow and expand it to be able to move better, with more ease, or to get better at a sport or activity. And we can tune into this sense by bringing awareness to our body and breath, and even with interoception have a sense of our visceral selves and internal machinations. Study of the body is endlessly fascinating:)

This makes me think about my aging parents and how, when their bodies slow down, the brain seems to slow down with it. There’s very little movement, so the overall awareness around space and even time disappears. I mean, they’re not that bad, but you can see the changes happening. And you can see how falls happen because the body isn’t used to moving in unexpected directions or different shapes anymore.

After reading this blog on Propeoception, I’ve come to realize that it is very much used in Yoga-Nidra, and also Progressive-Muscle-Relaxation! These types of practices are a treat for the body, mind, and soul!

Formidable article pour mieux comprendre la proprioception. À lire et relire!

I just registered for the November Nashville training & am excited!

Cet article est riche en apprentissage. Il m’a permis de developper mes connaissances sur la proprioception et me donne envie de continuer à en apprendre encore plus. Il a été aussi source de prise de conscience. Je viens de comprendre qu’il y a de ça quelques années en arrière quand j’étais si mal dans mon corps, j’étais complètement déconnecté de mon corps, j’avais l’impression de ne plus l’habiter…Pas étonnant vu cet article car à l’époque j’étais carencé en vitamine B12 du coup ma proprioception était altéré voir inexistante. Ça fait tellement de bien de comprendre ce qui nous arrive ou qui nous est arrivé. La comprehension me donne un certain pouvoir car LA PRÉVENTION COMMENCE MAINTENANT

Mon coup de cœur pour cet article qui fait le lien entre la proprioception, la douleur, une carte de développé dans le cerveau. Merci pour les références qui nous permettent d’approfondir les connaissances sur ce sujet. J’ai aimé les conseils pour améliorer notre proprioception.

Wow! “Pretend your brain is a finger.”

Toujours très intéressant et pertinent ! Merciii !

Très utile en tant que cavalière, je comprends mieux l’intérêt d’une bonne proprioception.

Merci pour cette article très intéressant, je n’avais pas intégré cette notion dans ma vie quotidienne et cela me donne désormais envie d’observer davantage. Isabelle

This looks very interesting!Thank you for the interesting explications and practical applications about the relation between proprioception, mobility and pain .This article has helped me have great ideason how to improve proprioception !

J’adore! Important de mettre à notre horaire les exercices de proprioception surtout en vieillissant et après une opération. Connaître ce que notre cerveau comprend quand on ne bouge pas…ou que l’on a peur, car nous avons mal est impressionnant. Donc, bougeons et comprenons la relation de notre corps avec l’espace.

Just loved this super informative article on proprioception and the importance of truly knowing where your body is in space. Especially the explanation from Lilah. Kids are the best and so pure especially when it comes to explaining and understanding things. I also enjoyed reading others beliefs and perspectives on proprioception. GREAT READ!

“Know where your body is in space” is a new mantra of mine. Great read!!

After reading this article, there is a lot more to proprioception than I previously thought. It amazes me how it can deteriorate through daily activity but yet can be easily countered with daily strategies to not only decrease chronic pain but also to ease you into older age with greater awareness to prevent injury such as falls.

I am excited by the idea that the better one’s proprioception and interoception, the less likely to sustain injuries. This connection is obvious when describing the ankle stepping off a curb but is more subtle when considering any type of movement that may slowly be causing harm – like sitting too long. For many repetitive daily movement patterns, like posture, my cognitive understanding of what is good posture provides information about how to avoid harm and it would be awesome if I received that info directly from body proprioception and interoception and made adjustments automatically.

I learned a great deal through this article and more everytime I re-read it. The part where it explains the relationship of pain and proprioception is in particular a personal experience for me. I injured my left shoulder few years ago and had knowingly and unknowingly “pampered” it way too much even after it recovered. Today I experience lack of strength and propioception on my left shoulder as compared to my right one. I’m so glad to have read this article that shines a light on the issue and how to work on rectifying it.

Wow! Such an incredible article on a very important subject for athletes (especially the hockey players and combat athletes I work it). Definitely saving this for reference and to revisit for such great information on how to improve proprioception with them.

Wow wow wow…lots to process, re read, and investigate here. This is an article I will be referencing for a long time….and the videos!!

This is an absolutely fascinating article about the relationship between proprioception and pain. While I have been introduced to some of the general concepts of proprioception discussed here, I have never so succinctly read about how pain takes up brain capacity which then reduces capacity for proprioception. Additionally, as someone who has developed some degree of hypermobility from 25 years of intense yoga practice – I felt unsettled and frequently ran into things, fell down or felt off kilter physically/emotionally/mentally/energetically until I began lifting weights and receiving regular touch therapy in the form of massage and physical therapy. This article helps me understand better why I became a bit “clumsy” through my hypermobility and couldn’t ever find a place to rest, and why the stabilizing exercises in my current movement diet are so helpful for my proprioceptive abilities!! The videos embedded here are awesome too and I really felt how they changed my mapping of different areas and coordination quite quickly.

I love the balance work shown in the video! So many can benefit from such a simple thing, standing on one leg!

Regarding the loss of proprioception due to injury or protecting a joint, has there been a study or is there general information about how much proprioception and/or mobility can be regained and over how much time? Is there a point of no return?

Proprioception is such a CRAZY thing! Like your brain plays tricks on you all the time. I read in some of the comments about accidents and being an amputee, it’s so interesting how everyone has such different levels/experiences with proprioception. When I was reading through the article, the author wrote about dancers needing to to be close to something, I realized that i grab my kitchen counter every time i walk by it so I don’t run into it. Your brain adapts and protects you so quickly!

Some years ago I had spinal surgery and as a result, I Iost some proprioception in my feet and buttocks. Initially I was a bit freaked out with this new body I learned to ignore it and keep on going. Since then, I have learned more about my body and this phenomenon. This article has helped me have a stronger understanding of that/this experience.

my cousin was an amputee. she had phantom limb syndrome. i’m wondering, if the map of her amputated leg is still there when the limb isn’t, how that ever ends? it did end in my cousin’s case, but i’d like to understand why. Thanks.

This is so eye opening….lol. I honestly never could wrap my mind around proprioception and now I feel like I have so much information to share! After knowing many older family members and their falls, it seemed inevitable. Yet now I am enthusiastic to be diligent now to nurture my body awareness and create space for shifting perspective of getting older into getting wiser.

Thank you for explaining the pain cycle: pain leads to lack of movement leading to poor proprioception leading to more pain. The inverse, encouraging movement and balance exercises to improve proprioception to reduce pain seems so simple after reading this article. The article comes together so organically.

So many interesting ideas – and practical application – sensing ones body and being able to right ourselves if we are on an uneven surface – our mechanoreceptors that are also involved in acceleration – stopping ourselves from “going down” or knowing (and having the physical ability) of when we need to speed up – all to keep ourselves in a position where we wont hurt ourselves, or can do our task as athletically as possible – be it sports, lifting boxes, whatever… But what about the idea of pain – and the more pain, the less we move, and then the less connection-firing-messages-receiving messages-pathways- beginning parts of the message transmission line- ending part of the transmission line – which is it? all? so complicated and cool!

So – what about the person who is just a “klutz”? Two left feet” Has “dropsy” – either always been that way, or when growing? (my son was always bumping into things during growth spurts – and many glasses of milk were on the floor…. what was happening with proprioception then?

Regarding the blog idea of the piano player having a larger brain map area dedicated to the hands – what about the other parts of the pathway? is it for sure the brain, or could it be in the pathways, receptors, etc?

Wonderful blog! Love all the videos that supplement what you’ve written. I found the video about slow rolling & isometrics and tapping & plyos a great way to bring to life the concept of sequencing manual therapy and muscle activation. Thank you 🙂

Wow! Thanks for this article. I am always amazed at the results when I use the YTU balls. An instant improvement in my proprioception but also a reduction in pain. It’s a wonderful gift to give yourself! Practice, ride and listen to yourself!

Great self-test for proprioception! It’s important in all spheres of our lives.

Great article, I use a balance trainer like this: https://kitsuneyoga.com/all-about-balance-trainers-and-half-balls/

My balance is poor, and I never thought that I could do anything about it. This looks very interesting!!

Fantastic article!- such clear information, love all the quotes from the experts and all the helpful hints on the You Tube clips. Thank-you!